Is there a way forward?

“All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory”: this is the first sentence of Viet Thang Nguyen Nothing Ever Dies (2016), about the dispute for memory in the Vietnam war. This adage can also be applied in the current struggle in forming a public conversation about historical memory in Spain. Much like wounds need to be sanitized before they can properly heal, the past often needs to be addressed in order to be able to move forward. If these crimes and executions are still a matter of contention nowadays is because of the Amnesty Law of 1977, that prevented the prosecution and trial of any crime related to the dictatorship era. Many decades of inactivity towards any kind of investigation by the Spanish government of the crimes committed by Franco's dictatorship could be considered part of the “structural violence caused by the bureaucracy and especially, recordkeeping” (or a lack of thereof) Gilliland and McKemish mention when, in a similar historical context, they reflect on the aftermath of the Yugoslav Wars (111). Archives, records and data can be and usually are tools to determine who controls the narrative that the mainstream collective memory discourse takes, particularly on an institutional level. Even after the democratic transition, Preston points out (32), it was not until 1985 that the Spanish government started to take steps to protect the state archive’s resources. In this context, any kind of action with the goal of giving visibility or investigating these crimes is already a conscious effort to partake in this conversation.

Labanyi reflects on if there’s any forgiveness and reconciliation possible after the Amnesty Law of 1977, especially since when it comes to distributing responsibilities, this area that has barely been broached in Spain, “unlike Germany, France or Holland, where there has been a considerable debate on the widespread complicity with Nazism of the population at large” (199). She addresses the issue of the power imbalance between victims and perpetrators citing, for example, the strategy to depoliticize the narrative in collections that compile the atrocities Republicans committed during the Civil War, and those that equalize both sides present the Civil War as a time of collective madness in order to avoid any kind of responsibility for the insurgent side. The question implicit in Labanyi’s writing is, then, how can there be forgiveness and healing when, for more than sixty years, there has been a lack of interlocutors that are willing to assume any kind of responsibility. In fact, she points out that not only there were no official attempts to any type of investigation, but that there also have not existed any steps towards reconciliation (201-3).

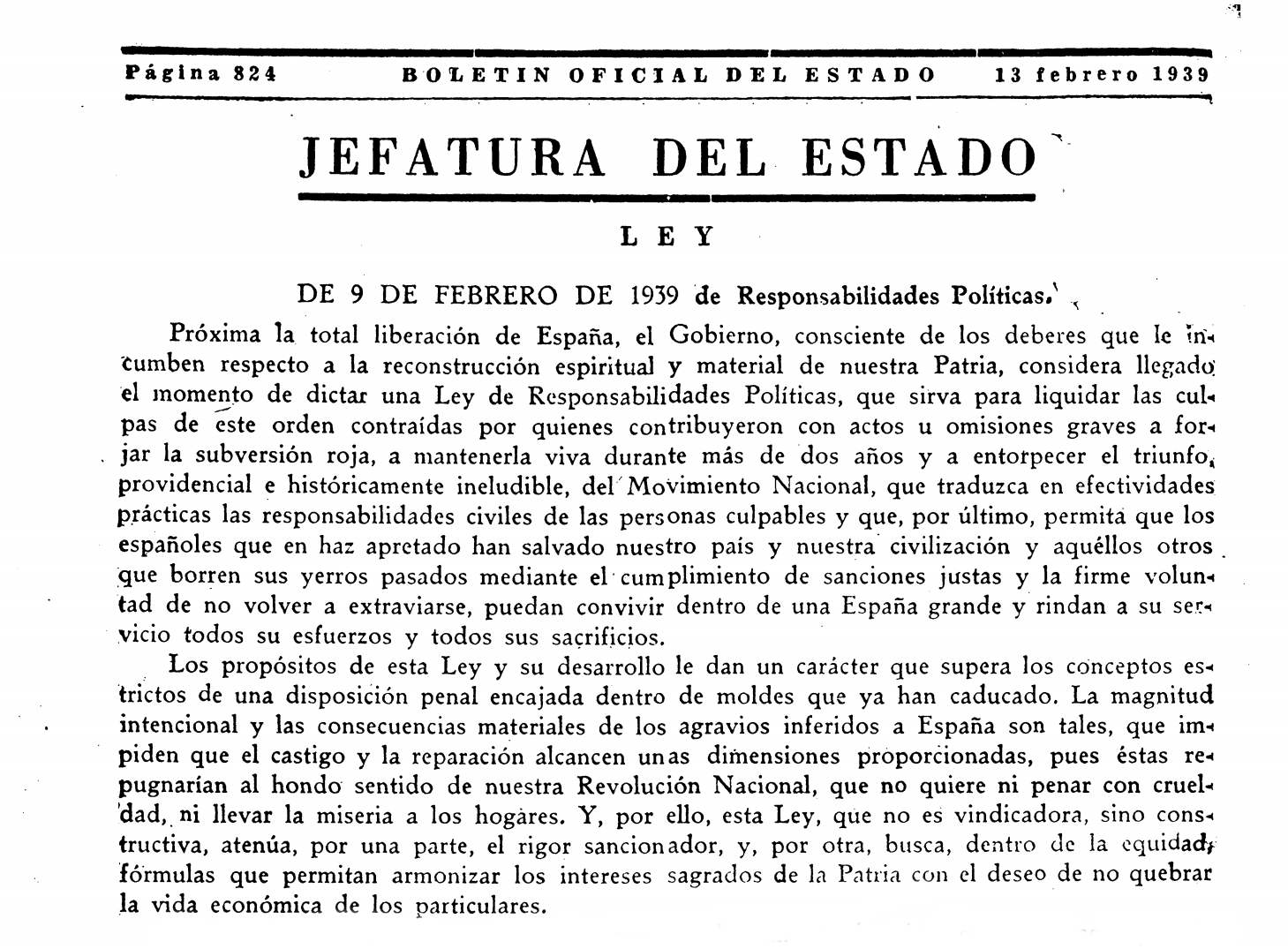

So far, the amnesty is still in place, and the new Historical Memory Law proposed in 2020 in the Spanish Parliament has sparked a fiery debate. On both occasions (2007 and 2020), the strongest opposition to these Laws of Memory has come from the conservative Partido Popular (amongst the founders of which there are well-known members of the Franco executive, led by the Francoist Minister for Information and Tourism (1962-69) Manuel Fraga Iribarne). In 2007, the then party spokesperson, Ángel Acebes, declared that the law "was a profound mistake” that supposed an attack to “everything the Democratic Transition represents” and that focused it on “remembering the worst of our history instead of highlighting the best” (20minutos, 10/09/2007). Nowadays, the conservative party maintains the discourse that looking back is a disservice towards reconciliation, and it is joined by the extreme-right party Vox, which in October 2020 demanded the derogation of the latest Memory Law saying it is “a threat to freedom of expression”, and that Lluís Companys should be recognized as “one of the main murderers of the Republic and Catalonia” (Tolosa, El País, 10/13/2020). On the other hand, there have been petitions to derogate this amnesty and calls to action to investigate Franco's administration crimes; international ones, like U.N.’s call to revoke this so-called “deal of silence”, as well as calls from the republican leftist party Unidas Podemos, as well as multiple Catalan and Basque nationalist parties. In fact, it was the coalition of Junts Per Catalunya and Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, both parties with a nationalist and secessionist agenda, those who drove the piece of legislation that passed in the Catalan Parliament in 2017. It acknowledged, for the first time on an institutional level, that the names that appear in the dataset as victims of war crimes, rather than the perpetrators of them. This attests to the difficulty of this topic still in present day Spain and the significance of contesting the decades-long official narrative of oblivion through the research, analysis and conversation to counterbalance decades of silence.